June 12, 2017

5 common myths about learning to read

Teachers and tutors know that there’s an art to teaching reading. Not all students engage with the same types of books, and different techniques may work better with some readers than others. However, common misconceptions about learning to read can create unnecessary barriers for young students. Explore the facts about five common reading myths.

Myth 1: Learning to read is a natural process.

In truth, learning to read is a skill that has to be taught and developed—it doesn’t occur naturally. It would be unfair to assume beginners at any skill, from riding a bike to watercolor painting, should catch on naturally without a whole lot of instruction, examples, and practice. Oftentimes, folks equate learning language with learning to read, and while learning to speak is a natural process, learning to understand written text is a completely separate skill set. Reading Rockets emphasizes that “Spoken language is ‘hard-wired’ inside the human brain. Language capacity in humans evolved about 100,000 years ago, and the human brain is fully adapted for language processing.” Learning to read, on the other hand, is not yet hard-wired in the brain—consider that humans have only been reading and writing for a fraction of human history.

Myth 2: Weekly vocabulary lists are effective.

While many of us likely went to schools where memorizing weekly vocabulary lists was a norm, it turns out that this may not be the most effective way for students to learn and retain new words. The Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development writes that “Learning anything, including new words, involves connecting or integrating the new information with what you already know.” This means that learning new words in the context of authentic texts and content area instruction such as science and social studies can be more effective than rote memorization.

Strategy: Create a word journal where you can write down new words as they arise. Keep the journal close by when reading aloud and add new words during story time. Remember to use these words in different contexts and use creative vocabulary review activities to check for understanding on a regular basis. Here are some examples:

- Act out the word “active”

- Draw the word “active”

- Yes or No game: Is the desk “active” (yes or no)? Is the football player “active” (yes or no)?

Myth 3: Readers who are behind should master literal comprehension before inferential comprehension.

At first, this myth might seem logical: shouldn’t new readers focus on the details like recalling characters and setting in a story? While it’s true that understanding and remembering these elements of story are important foundations of reading, developing readers are often able to go beyond when supported with appropriate questions. Education leaders and researchers have found that background knowledge makes a significant difference to reading comprehension. Often, struggling readers are able to draw inferences from a text by drawing on prior knowledge and combining that with information in the story, leading them to deeper understanding of a story’s message.

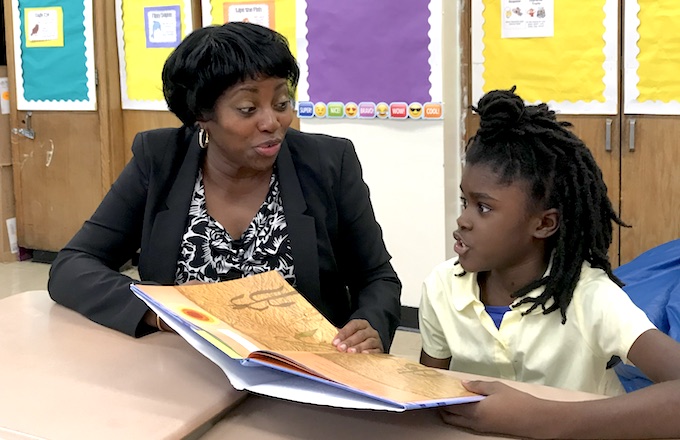

Strategy: During a read aloud session, use questions to encourage making inferences.

- What do you think the author meant by…?

- Why did the character do….?

- What is happening here?

Myth 4: Looking back during reading reduces comprehension.

Looking back to answer comprehension questions isn’t cheating. In fact, encouraging readers to look back can reduce barriers to comprehension as it can illuminate where a misunderstanding has occurred. This has another important implication, as students who look back in a story to find an answer are also developing critical problem-solving skills. Rather than taking a shortcut, readers who look back are building the habit of using evidence to support answers, rather than guessing.

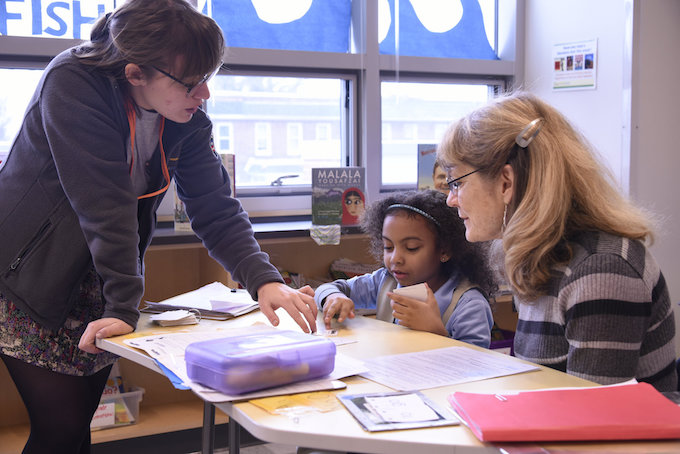

Strategy: Does the book you’re reading with your child have a map, a family tree, or a glossary as a reference? Take some time to flip back to those pages together when a question comes up about something that happened in the book to find evidence for your answers.

Myth 5: Real understanding of a text comes from finding the author’s precise meaning.

Adult readers know that any story or book can be interpreted countless ways—as many ways as there are readers. What makes these interpretations valid is supporting them with evidence, whether by looking back in the text or by drawing from life. Little ones learning to read should be encouraged to apply their personalities and backgrounds to their understanding of what they read since that’s when reading is at its most powerful. A study revealed that strong student responses to stories “include specific retelling of the text…explicit connections between their personal experiences and their interpretations.”

Strategy: As you are reading, take a few minutes to draw parallels between the story, characters, setting, and your life. For example, in the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, you can ask: “Is Jack lucky or smart?”