September 27, 2013

Discussing Diversity in Children's Literature

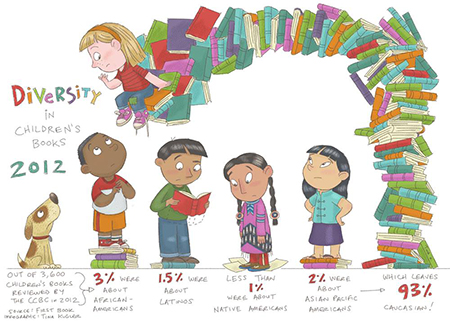

This beautiful illustration by the talented Tina Kulger, inspired by data collected in the most recent study from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, has brought renewed awareness of the troubling reality of underrepresentation of African-American, Asian, Native American, and Latino/a characters in children’s books. What can or necessarily should be done with this knowledge has been the subject of much debate.

Brooklyn author and illustrator Christopher Myers posted an excellently penned essay on the matter in Horn Book Magazine. In it he argues that literature “allows us a bird’s-eye view of our own lives, and especially how our lives relate to those lives around us” and reminds us of the power of books to favorably shape how our encounters of “others” will transpire in real life.

So here, then, is my responsibility. To make images, to tell stories, to trouble the narratives that pervade so many people’s secret hearts and minds. To make books in which black people are not flat emblems of our divided nation, flag bearers for guilt or fractious history, but instead humans full of laughter and love and care for one another and their diverse communities. To augment and enrich the image libraries people carry in their hearts; to give them more than slain civil rights leaders and escaped slaves, people whose lives are steeped in violence both literal and figurative, akin to a McGuffey Reader of tolerance and just as desiccate. Instead, I want to give my readers spaceships, clowns, and unicorns, to depict whole human beings, to allow the children in my books to have the childhoods they ought to have, where surely there are lessons and context and history, but there is also fantasy and giggling and play. To encourage them to open their hearts when they see someone who looks like me, even if that person is in the mirror.

It is a responsibility I hope we share, all of us who love literature and children. It is the responsibility that lies behind the percentages, behind the numbers, beyond the market. When we make books, or write about books, or purchase books, we are affirming a vision of the communities in which we want to live. Through books, we outline a vision for our future. We can no longer stand for our futures to be isolated, segregated, lonely, and angry. We can no longer turn a blind eye to stories that create worlds in which difference is viewed as a burden, a dry educational tool, a threat — or, worse, is simply rendered silent and invisible. Those fictional worlds have very real effects. There are children with fear in their hearts, there are children in caskets, and it is up to us to help the next generations avoid those fates.

Young Dreamers (via Horn Book); Illustration by Tina Kulger