Closer to home: The shrouded consequences of pollution on children’s academic success

April 17, 2023

Volunteer coordinator, Reading Partners New York

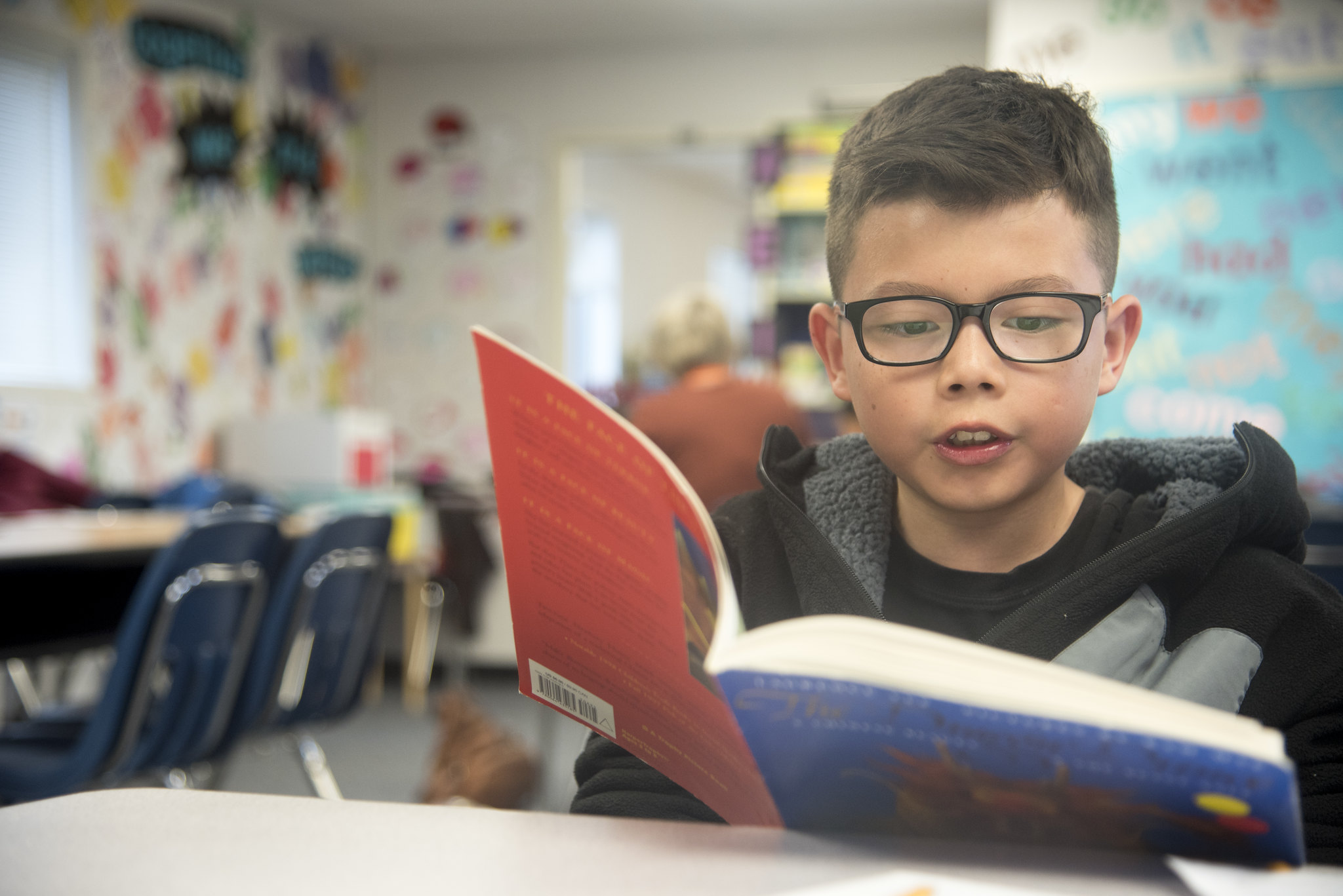

Children across the US are faced with obstacles that they cannot control. Their schools are constantly being defunded, their class sizes are increasing, their teachers are either leaving or being let go, and they are losing out on crucial resources like access to wifi and technology that are necessary for young students in the 21st century. Because of these obstacles, students don’t have the resources and support they need to succeed in the classroom and beyond.

Some may assume that these are the only obstacles children face in the classroom. That the issues that weigh down our educational system are confined to the educational sector. But students face greater, more subversive barriers to academic success than are immediately apparent. As a nonprofit dedicated to literacy, it is important that we talk not just about the obvious academic challenges, but about those challenges that are indirect and hidden, and thus all the more dangerous.

Research has continuously shown that air pollution and rising global temperatures both disproportionately harm children, and diminish academic success. The New York Times reported in 2019 that children are “more susceptible to fine particulate pollution” and are “more likely to suffer from the effects of extreme heat associated with climate change” because of a combination of factors ranging from the amount of time they spend outside, to physiological differences in things like heart rate. This means that children, more than adults, will suffer from the immediate effects of rising temperatures, and the long-term effects of continuous exposure to harmful pollutants in the air.

Pollution and student outcomes

Sustainable school buses

As a literacy organization, these health effects matter because they create educational disparities. Children living in communities with higher pollution levels and less access to affordable and sustainable transportation experience academic setbacks at a disproportionately higher rate than children living in safer, more sustainable communities. A recent study looked at a comparison among children who attended schools with diesel-based school buses that retrofitted their exhaust systems to become more sustainable. Researchers were able to study students’ test scores before and after retrofitting these buses in order to measure the difference in academic achievement among children who were subjected to greater, and more harmful forms of pollution.

Photo by Vlada Karpovich

Researchers studying this effect in Georgia came to the following conclusions:

Retrofitting 10 percent of a district’s fleet increases English test scores by 0.009 standard deviations, so retrofitting an entire district’s fleet would increase test scores by nearly one-tenth of a standard deviation. Weighting by the share of students who ride the bus, we find that districts experience a 0.14 standard deviation increase from retrofitting an entire fleet when all students ride the bus.

These were statistically significant increases in test scores once students lived and traveled in communities with more sustainable buses, and these increases came specifically in English where the improvements were most noticeable.

Air pollution and hazardous waste sites

Researchers at the National Bureau of Economic Research also studied the “effect of school traffic pollution on student outcomes” by looking at the difference in test scores and academic achievement among students who moved schools and transitioned to schools downwind of major highways into areas with higher levels of air pollution. Their research found that:

attending school where prevailing winds place it downwind of a nearby highway more than 60% of the time is associated with 0.040 of a standard deviation lower test scores, a 4.1 percentage point increase in behavioral incidents, and a 0.5 percentage point increase in the rate of absences over the school year, compared to attending a school upwind of a highway the same distance away.

Those same researchers have shown similar effects among children living near more direct forms of pollution like abandoned hazardous waste sites. They found that “children living within two miles of an uncleaned Superfund site had a 23% increase in cognitive disabilities like learning disabilities, autism, intellectual disabilities, and speech and language impairments.”

Photo by Tom Fisk

While research is limited, these three studies alone show a concerning connection between pollution and child academic success. Whether it’s learning disabilities or lower test scores, students and children face detrimental, life-altering obstacles to their schooling as a direct result of pollution.

And the harms do not stop with test scores and learning disabilities. Declining test scores lead to less public school funding and fewer resources. It means we have to ask more of our teachers and our administrators in both concrete resources and emotional energy, which means less individualized instruction for our students. It means widening gaps between those students who face barriers to academic success, and those who do not. And it means students who fall behind are left behind. These problems, the ways pollution harms our students, can feel insurmountable. Problems that feel so grand and unassailable that coming up with solutions feels trite and unhelpful.

So, what can we do?

In August 2022, the Biden Administration passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Notably, this act contains the largest share of resources dedicated to climate change and environmental solutions in history. Beyond grants and tax cuts that corporations can benefit from by reducing their carbon footprint and becoming more sustainable, the act specifically names solutions to both transportation accessibility and sustainability. The IRA is dedicating one billion dollars towards clean, heavy-duty vehicles like school buses, transit buses, and garbage trucks. These solutions are also being concentrated in communities that need them the most. The IRA is specifically focusing on “disadvantaged or underserved communities” by creating “equitable transportation planning and community engagement activities.”

Making buses more sustainable and reducing their emissions is essential, but buses and heavy-duty transportation only account for approximately 30% of air pollution. What is even more essential is equitable transportation planning. The more interconnected and accessible our transit systems are, the fewer personal vehicles we will use. Personal vehicles account for over 50% of U.S. emissions, making them by far the biggest polluter. The IRA addresses both of these facets of transportation emissions. It is not just that the bill provides large swaths of money dedicated to the issue, it does so in a way that tackles multiple problems at once, and tackles them at the root.

Bills like the IRA are important for our planet at large, but they are also important for our communities and our students. Climate change is inextricably linked to the health of our communities and the success of our students who are already beset by a plethora of obstacles and barriers outside of their control. When we pass sweeping climate legislation that dedicates large swaths of funding and resources to this grand environmental problem, it has positive effects that reach far beyond immediate environmental damage.

All this to say, this discussion is not meant to dissuade or discourage environmental policies that are meant to aid and assist the global community. Climate change is one of the greatest threats to global health, and will create disastrous consequences for communities around the world, leading to climate refugees, displaced communities, and destroyed countries. This discussion is meant to show that the issues that affect the global community, and the solutions that alleviate those problems, are also important domestically. Bills like the IRA let us both protect the world in which our children grow up, and create environments where those children can succeed and thrive.

Citations

Austin, Wes, Garth Heutel, and Daniel Kreisman. “School Bus Emissions, Student Health and Academic Performance.” Economics of Education Review 70 (June 2019): 109–26.

Persico, Claudia. “How Exposure to Pollution Affects Educational Outcomes and Inequality.” Brookings, November 20, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2019/11/20/how-exposure-to-pollution-affects-educational-outcomes-and-inequality/.

Persico, Claudia, David Figlio, and Jeffrey Roth. “The Developmental Consequences of Superfund Sites.” Journal of Labor Economics 38, no. 4 (October 2020).

Pierre-Louis, Kendra. “Climate Change Poses Threats to Children’s Health Worldwide.” The New York Times, November 13, 2019, sec. Climate. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/13/climate/climate-change-child-health.html.

Simon, David, Jennifer Heissel, and Claudia Persico. “Does Pollution Drive Achievement? The Effect of Traffic Pollution on Academic Performance.” National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2019, 63.

“Summary of the Energy Security and Climate Change Investments in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022,” n.d., 4.

US EPA, OAR. “Fast Facts on Transportation Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” Overviews and Factsheets, August 25, 2015. https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/fast-facts-transportation-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

Banner photo by Pixelbay