July 11, 2022

What Everyone Can Learn From Leaders of Color

From Stanford Social Innovation Review

By: Darren Isom, Cora Daniels & Britt Savage

Hector Ramon Salazar vividly remembers the moment that brought him to his leadership role at Reading Partners, the national literacy nonprofit. It was the Saturday after Thanksgiving, and he was standing at the intersection of 35th and Foothill in East Oakland, where, despite encroaching gentrification, the faces are still Black and brown and resources are still needed. It is also the community Salazar calls home—that day, he was out getting a propane tank for the family’s grill. Salazar is first-generation Venezuelan American, identifies as Latino, and is profoundly proud of his “South American Caribbean heritage and bloodline,” which also shapes how he approaches leadership and social change.

Standing at that East Oakland intersection, Salazar got the offer to join Reading Partners as executive director of its San Francisco Bay Area program office. Well, let’s hear him tell it: “I was wearing my hoodie, sneakers, and beanie, my two youngest kids were running around in the background, I was surrounded by the sounds, the smells, and the energy of East Oakland, and I get the call. I thought for a moment and said to myself, this is what an executive director looks like,” he says, nodding his head as if he is looking himself up and down in a mirror. “And I have an obligation and responsibility to take this role and switch things up.”

The calls across the social sector to put BIPOC leadership at the forefront have always been there for anyone willing to listen. The case for the importance of proximate leadership for the sake of impact has been made many times over. Bias-fueled myths about the lack of qualified leaders of color have repeatedly been debunked. This article does not attempt to do any of that again.

But, through our work with clients and in conversations across the sector, we have heard a variety of questions in response to the calls to elevate leaders of color that we feel are important to address. Such as, “How do we make sure things at an organization meaningfully change besides just the faces around a table?” and, “Does the diversity of leadership really matter if an organization already factors race into its strategy?”

Questions like these arise not necessarily because people do not value diversity, but because they seek, lack, or struggle for deeper understanding. So, this article is about the assets and skills leaders of color bring because of their identity that make them effective leaders. How, as Salazar says, they “switch things up.”

“If I have to leave out the part of myself that is positively identified with being Black, then no matter how good I am, I am not the best I can be,” says David Thomas, the president of Morehouse College and an internationally recognized expert in organizational management and leadership. “I know the power of bringing all of myself, and it becomes a tool that, quite frankly, advantages me over a white guy who has never had to think about his identity.”

Let’s be clear: Thomas is not suggesting that Black leaders, and leaders of color more broadly, are inherently better than their white counterparts. Nor are we suggesting that people of color inherently lead differently by virtue of being born a certain race or ethnicity. Rather, the ways people of color have experienced the world up to this point can affect how they lead. This goes beyond experiences of oppression or historic marginalization to include the connection, meaning, and joy these leaders can draw on from their respective cultures and communities. As a result, there are assets and skills many leaders of color develop and excel at because of the experiences and perspective their identity brings.

Granted, race and leadership can both seem like amorphous topics, each complicated by their deeply personal natures. To better understand the relationship between leadership and identity, we talked to 25 leaders of color across the sector, including both nonprofit and philanthropic leaders, as well as engaged leadership experts, and read up on the latest leadership literature. In this effort to more fully explore what successful leadership looks like, we also created a podcast, “Dreaming in Color: Creating New Narratives in Leadership,” to host conversations with leaders of color discussing issues of identity and leadership. Overall, our research identified several noteworthy assets, insights, and themes that many of these leaders of color share.

These assets can often be critical for social change. We hope this prompts the sector to rethink what the norms of good leadership might look like if the sector valued the assets of leaders of color—indeed, if it placed those assets at the center of the sector’s leadership norms.

With that in mind, what if the sector’s animating question when it came to leadership became: What can every leader and organization learn from BIPOC leadership?

How Leadership and Identity Are Intertwined

Not surprisingly, just as the systemic nature of racism infects society’s structures, institutions, and philanthropic giving, so, too, does it shape attitudes about the skills and assets leaders need to be effective.

Consider that, according to research conducted by the Building Movement Project, people of color have represented fewer than 20 percent of nonprofit heads for the past 15 years, despite an increasingly racially and ethnically diverse nation. Similarly, under 25 percent of board positions are filled by people of color. The picture is even starker when looking at BIPOC leadership in philanthropy: In 2021, the Council on Foundations found that only 12.1 percent of leadership roles at foundations were filled by people of color.

Now consider what it must mean for social change when definitions of good leadership are inherently biased and shaped by dominant culture norms. “Often people will look to Native leaders and dismiss their experience as limited to Indian country, as if that is less than. It shows no understanding of the complexities of what it means to work in Indian Country,” says Raymond Foxworth, vice president of grantmaking, development, and communications for First Nations Development Institute and a member of the Navajo tribe.

“We are in a sector that supposedly values social innovation, but then are missing the genius that comes from being a part of communities that have survived in spite of direct government policies seeking to remove language, culture, and identity. Survival shouldn’t be a baseline, but Indigenous survival didn’t happen by accident. It happened because people were innovative in protecting Indigenous knowledge and belief systems and shielding it from a colonial and corrupt system that’s out to destroy those things. If people survive state-sponsored genocide, as Native people have, innovation is at the heart of their existence. Those are the leadership lessons I bring with me.”

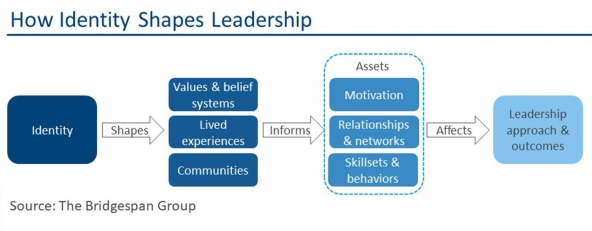

As Foxworth points out, leaders are not solely a product of internal drive; they are also a result of lived experiences, external investment, and recognition. In other words, leaders are made, not born. A person becomes an effective leader through the people that support them and the opportunities and experiences—both good and bad—of their life and career. This combination allows for new skills to be developed, old skills to be honed, and potential to shine through. In the figure below, we’ve laid out how identity, including racial or ethnic identity, as well as other dimensions, such as gender, sexuality, and class, can influence a leader’s approach to their work.

Aspects of identity such as race and ethnicity can shape the values and belief systems a person is taught, the lived experiences they have, and the communities they claim and that claim them. In turn, those things inform what motivates a person to pursue their work, the relationships and networks they choose to cultivate, and the skill sets they develop and behaviors they adopt. Altogether, that affects the decisions a leader chooses to make (or not make), the strategies and solutions they develop, and ultimately the outcomes they achieve.

Of course, identity is not the only factor—formal education and training, for example, play a meaningful role in the skills, behaviors, and networks a leader possesses. Racial and ethnic identity is not a monolith either; intersectionality of identities shows up differently in every individual.

But based on our research and client work, we see that identity can also be a significant influence, one that is often overlooked or undervalued. While studies have demonstrated the power of proximate leaders, they haven’t yet gone very far in understanding the specifics of that power and the attributes those leaders are bringing to the table.

Lessons We Can Learn From BIPOC Leaders

When we studied the motivations, relationships and networks, and skill sets and behaviors of BIPOC leaders, we found strengths that are particularly well suited for social change. In some cases, these strengths are evident among good leaders of all identities, but may manifest differently in leaders of color. Other assets are uniquely based in identity and therefore are more common in the leadership approaches of people of color.

Motivation

One of the most common things we heard from leaders of color was that they felt “called” to their work. Some spoke about being driven by a desire to address challenges that they themselves or their community experienced, often as a result of racism or other forms of oppression. While the value of proximate leadership has been embraced by many across the sector as a path to better solutions, less recognized is how motivation can be powerfully strengthened by that proximity.

“There is love and a level of responsibility that I feel I have to give back to my community because I’ve been given so much, maybe not materially but in other ways,” says Foxworth of First Nations. “My sense of responsibility also shapes how I approach the work by always listening to communities, valuing that knowledge and that perspective.”

That sense of community responsibility that can shape leaders of color can be paid forward, too. “It is not just ourselves. It’s all the people that you’re kind of carrying their future legacies with you,” says Nate Wong, former chief strategy and social innovation officer at the Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation, who is ethnically Chinese with parents from the Fiji Islands and Hawaii. “I don’t take that responsibility lightly. I definitely want to show a different model of how leadership might look.”

In fact, many leaders of color we talked to measured their own success less in individualistic terms but more by standards of community power-building and liberation. For some, these collective values have been reinforced over a lifetime among families, neighborhoods, faith communities, cultural institutions, identity-based organizations, and affinity spaces. This embrace of collective success is particularly well suited for social change leaders, given that the work is about making the world better for all.

In addition, what often comes with this heightened sense of responsibility is a strong sense of accountability. In other words, the expectations of the community and to the community can hold these leaders accountable at a level that is critical to social change. Leading with this sense of accountability is at the foundation of how anti-racist organizations can be built.

This does not mean that leaders of color can only work on identity-related issues or lead identity-based organizations. Nor that they only want to do so. But the motivation of collective success and the accountability to community are strengths that these leaders can bring to any work they do. Likewise, those are assets that all leaders can learn from and develop.

Relationships and Networks

Given the demographics and power structures of the nation, people of color often learn out of necessity how to build connections across lines of differences, including with both white allies and other communities of color. As a result, research shows, their networks are typically more heterogeneous. That is a powerful asset to draw on to learn, grow, access opportunities, and navigate challenges that arise. Kyle Dodson, the CEO of the YMCA in Vermont’s Greater Burlington area, often finds himself the only Black face in powerful rooms in the overwhelmingly white region and sees himself as a bridge between communities.

At the same time, by authentically drawing on their identities and lived experiences, these leaders can build trust with the communities that social justice efforts are often working in. Andrea Caupain Sanderson, a Black woman and immigrant from Guyana who is CEO of Byrd Barr Place, a historically Black-led organization that provides food and shelter to those in need in Seattle, was a client of the food bank as a child and so had an understanding and trust of the community at an intimate level. Those authentic relationships led Caupain Sanderson to discover that the food offerings were not adequate for families to thrive. So she overhauled how the food bank operates. The organization stopped accepting food donations and started fundraising to buy food that is more nutritiously balanced and culturally compatible.

More important than simply having diverse networks is the ability to then recognize, value, and tap into what each person brings to the table. This can mean leaders of color are good at drawing lessons from nontraditional places that often subvert hierarchical limitations.

“The power of being an outsider is you are constantly building your own alternative. My models for leadership were not conventional sources because [those in power] didn’t sound the way I wanted to sound and say what I wanted to hear,” says Urvashi Vaid, an Indian American LGBTQ rights activist and social movement strategist who co-founded the Donors of Color Network and has had leadership roles in philanthropic, advocacy, and community-based organizations. (Vaid passed away soon after our interview. To hear more from her on the leadership lessons she learned from protest movements, community activists, and everyday women throughout her life, listen to her episode of our podcast.)

We also found that being able to hold together relationships from such diverse networks helped these leaders recognize the power of an ecosystem beyond their organizations. Their leadership often includes collaborating with peers and other leaders for a greater purpose and encouraging their staff to do the same.

“A priority for me is getting our team to see who we are in the bigger picture,” says Salazar of Reading Partners. “A lot of nonprofits see themselves as the movement. A big shift I am trying to do on this team is for them to see that we do something really well, but we are a small piece of a much larger ecosystem. And there is power in that. The movement is social justice and education equity; the movement is not Reading Partners. If we are going to truly be part of the community, then we have to see we are part of something much larger.”

Skill Sets and Behaviors

Part of the squishiness around the definition of a “good leader” is that there is no consensus regarding a universal set of characteristics one should have. The know-it-when-I-see-it approach often reinforces dominant culture norms and thus has narrowed the vision of what leaders can and should be.

With that said, there is some agreement that the qualities of good leaders show up in several dimensions, namely within themselves, with others, and with their vision.

Leading Self

Self-Awareness: The starting point for great leadership that experts often point to is a strong sense of self-awareness. The benefit of self-awareness is that leaders who better understand themselves will have a clearer sense of what they want to accomplish and what talents they bring to get there, as well as what talents they will need from others to help. Such awareness can be cultivated through self-discovery and deep reflection.

That kind of journey is familiar to many leaders of color, since it can be part of a lifetime of learning to navigate racialized experiences and white-dominant culture. W.E.B. DuBois famously wrote about the concept of “double consciousness,” or the idea that Black people have the ability to see themselves as they are and also see themselves how white people see them. To various degrees, all people of color can possess versions of double or even triple consciousness that come with intersectional identities.

Comfortable Being Uncomfortable: An advantage of not being a member of the dominant culture is the expectation of discomfort that being different might bring. This can lead to a heightened ability to adapt to new experiences, overcome obstacles, and see alternative possibilities. Innovation is often associated with fun and creativity, but those who study leadership say that, in reality, innovation can be taxing and uncomfortable.

A. Sparks, a long-time philanthropy executive who identifies as a queer, hapa (mixed-raced; her mother is Japanese American and her father is white), cis-gender woman, credits the intersectional lens her identity brings for her ability to comfortably navigate different spaces. “My identity helps me really see the inherent value in all people,” says Sparks. “So I am able to walk into a room and do the code switching of talking to somebody as a peer. Being able to be a chameleon like that requires deep listening with a level of respect to really adapt in those situations.”

Leading Others

Empathy: The leaders of color we spoke to demonstrate a high degree of empathy. Experiences of injustice and oppression and of being othered can create a greater recognition of the humanity of others. While this can provide obvious benefits to how these leaders approach the work (see “Asset-Based Lens” below), empathetic management of your staff allows individuals and the organization to better thrive.

These leaders go above and beyond to center the well-being, harm reduction, and healing of their teams and to create culturally sensitive workplaces. They also incorporate practices such as four-day work weeks, office-wide periods of mandatory time off, flexibility, and pay equity, while often honoring families and family time as well.

“I try to value the assets and backgrounds of everyone in my organization. I want our staff to feel like they can talk freely about who they are and feel like they are valued for the assets they bring to the social impact work we do,” says Amanda Fernandez, CEO of Latinos for Education, which works with educators, students, and families to build an ecosystem of Latino leadership in education. Fernandez, who is Cuban American, says she feels bicultural because she grew up in a Spanish-speaking household in a white area of Florida and often saw the treatment of her white-presenting mother change for the worse when people heard her accent. “We put a lot of focus on culture building and relationship building in our organization. To be able to share our cultural backgrounds, experiences, and traditions plays an important role for our team in feeling like they can bring their full selves to their roles and to our team.”

Observation and Active Listening: Observation and listening are often embraced in the work styles of BIPOC leadership, creating a more holistic understanding of situations. A high degree of self-awareness and experiences of othering can help develop these skills. “There is power in listening. And in Asian American spaces, not just listening to what is said, but listening to what is not said because body language and cultural interpretation is important too. You have to be able to hear that loud and clear, too,” says Kathy Ko Chin, CEO of Jasper Inclusion Advisors, who is Chinese American and grew up in Cleveland during the 1960s.

That ability to recognize what is not said is a valuable skill set that offers a leader insight. We found many successful leaders of color across various identities develop this skill as a result of navigating a lifetime of complex interpersonal relations and interactions that can be layered with implicit bias and power dynamics.

Collaborative Leadership: Tackling today’s most challenging problems often requires not just the work of one organization, one philanthropist, or one leader, but an entire ecosystem. Therefore, collaboration can be the key to unlock greater impact.

The relationships and networks of BIPOC leadership often give rise to updated models of leadership that embrace more collaboration. That might mean co-executive directors: for example, after Vu Le retired as its head, Rooted in Vibrant Communities radically reinvented organizational leadership by naming four co-executive directors. It might also mean the democratic and distributive power structures—think Movement for Black Lives—found in networks, coalitions, and collaboratives. Or it could mean leaders seeing themselves as part of a movement ecosystem, as Reading Partners’ Salazar notes.

Finally, it could mean a CEO who leads more collaboratively, encouraging authentic thought partnership and inclusive decision-making from across the staff. Linda Hill, faculty chair of the Leadership Initiative at Harvard Business School (HBS), calls this “leading from behind,” a phrase she borrowed from the autobiography of Nelson Mandela and that shaped her study of how other communities, cultures, and movements have championed collectivist leadership approaches. “Leaders can encourage breakthrough ideas not by cultivating followers who can execute but [by] building communities that can innovate,” she writes. “For leaders, it’s a matter of harnessing people’s collective genius.”

Leading With Vision

Asset-Based Lens: Seeing and valuing the strengths of a community, rather than defining it by deficits, can come more naturally for leaders of color because of their lived experience. An asset-based lens is a powerful approach for lasting social change, since it requires a systemic understanding of issues. Rather than blaming inequitable outcomes on individual behaviors that need fixing or changing, an asset-based lens recognizes the gifts and skills that all people and communities bring, and as a result allows the broken structures and systems that cause inequities to become clearer to see.

Empathy and an asset-based approach are intertwined, with each capable of unlocking the other. The same empathy that is so valuable for leading others can be a critical part of developing an asset-based vision for communities. “I always remind people that the most powerful weapon that we can use to advance justice is empathy,” says Nathaniel Smith, a lifelong Black Southerner and founder of the Atlanta-based Partnership for Southern Equity, which advances policies and institutional actions that promote racial equity across the South. “Empathy is the spark or the bridge that moves love into action.”

Radical Imagination: The “outsider” experience that comes with being a person of color can provide valuable perspective. As a result, many successful leaders of color can call on a deep understanding of how to navigate existing systems while also imagining something completely different from a status quo that has never worked for them.

“As a BIPOC leader you are often, in some way, on the outside having to look in and decode what the rules are for yourself and for BIPOC communities. That can manifest in compelling ways when it comes to leadership,” says Ify Walker, CEO of Offor, a talent broker firm that often places executives of color. Offor’s approach to executive search, including an unusually extensive vetting process of an organization before taking it on as a client, is shaped by Walker’s experience of being a Black woman and first-generation Nigerian American. “From BIPOC leaders, I see the power to understand the rules so they can first succeed and then challenge those rules.”

Radical imagination can also be seen in how A. Sparks leads the Masto Foundation, which was founded by her grandparents, who were among the more than 110,000 Japanese Americans sent to internment camps by the American government during World War II. Under her leadership, instead of starting with the way grantmaking has traditionally been done, the foundation rebuilt its giving process around the Japanese American tradition of “gifting,” which frames giving as an “expression of gratitude, respect, and a desire to contribute.” This means the funder is constantly trying to limit the amount of time and stress the process might cause grantees. Conversations replace formal grant applications, due diligence is focused on listening, and funding goes out the door within a month of grant determinations. All of the organizations the Masto Foundation supports are led by people of color and/or are members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Casting New Suns

Perhaps because so much of the social sector’s work has to do with society’s inequity—what is missing, the harm inflicted, problems to solve—there is a tendency to let the needs of life overshadow the gifts. Likewise, it is easy to think about a world in which the assets of BIPOC leadership are not recognized, potential is not reached, and impact is not achieved. We are all living in that world.

But what if, instead, we think about what is gained by BIPOC leadership—how might our organizations be different? How would social change be achieved? The Building Movement Project’s 2019 Race to Lead research provides a peek. According to the survey, people of color and their white counterparts fare better under BIPOC leadership: the survey revealed that staff overall are more satisfied and more likely to want to work for their organization over the long haul. They also reported feeling that they have a voice in their organizations and believed that their organizations offer “fair and equitable opportunities for advancement and promotion.”

“I think a bias the sector needs to debunk is we think the social-emotional skills, or the ‘soft skills,’ of leadership are a plus and not a must,” says Maria Kim, president of REDF, a national venture philanthropy. “However, these ‘soft skills’ of curiosity, intentional inclusion, wonder, and empathy are actually harder skills to develop, and so need to be valued more than they currently are.” Kim, a first-generation Korean American, credits the perspective her “hyphenated identity” brings for helping her cultivate these skills.

For Morehouse’s David Thomas, the key to good leadership boils down to how a person embodies excellence. “I don’t buy into the notion that Black people have to be better than white people [to succeed] because that would suggest that every Black CEO is better than every white CEO, or in my case that every Black professor is better than every white professor,” says Thomas, who was a professor at Harvard Business School for 22 years. “Of course, that is not true. But what is true is that I had to sustain being better longer so people had time to recognize it. And the only way to do that is if you are personally committed to being excellent, so even when you are not rewarded for it, you still wake up to be excellent.”

We entered this research with the hope that by highlighting the assets leaders of color bring, the sector might rethink what it values when it comes to leadership. The writer Octavia Butler once proclaimed: “There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” Fittingly, those words were from the final book she never finished writing in her Parable series. This idea of “new suns” is a powerful mantra for social change, since the world we would like to see hasn’t been built yet. Likewise, it makes sense that the leaders to get us there would “switch things up” a bit, too. Now is the time for “new suns.”