March 11, 2021

Black English and “Proper” English: The impact of language-based racism

African American Vernacular English, or Black English, is a group of rich, systematic, and highly innovative dialects passed down within Black communities across the US. But language-based racism continues to inhibit speakers of Black English from having their voices heard and respected in spaces dominated by Standard American English.

Black speech on trial

When Rachel Jeantel served as a key witness in the highly publicized 2013 trial of the killer of Black teenager, Trayvon Martin, she was met with hateful comments and criticism regarding her testimony. Not because her testimony was falsified or unwarranted, but because of her speech patterns.

Jeantel was the “star witness” for the prosecution. She testified for a grueling six hours, more than any other witness at the trial. And yet, her critical testimony went unmentioned in the deliberations of the jury.

Source: Rachel Jeantel on Trial, The New Yorker

Why was Jeantel’s crucial testimony ignored and even ridiculed in this way? Linguists John Rickford and Sharese King (2016) point to White suburban ignorance of Black English and general prejudice against—or outright hostility toward—those who speak it.

“In a sense, Jeantel’s dialect was found guilty as a prelude to and contributing element in Zimmerman’s acquittal.”

– Rickford and King

African American Vernacular English

Linguists use terms like African American Vernacular English (AAVE), African American English, African American Language, or Black English to refer to a group of dialects of English spoken all over the United States by many (but not all) Black people. AAVE is no more nor less complex, expressive, or systematic than any other dialect of any language, including Standard American English (SAE), the dialect commonly used in media, academia, commerce, and government in the US today.

Rickford and King’s careful analysis of nearly fifteen hours of recorded trial-related events show that Jeantel was not “inarticulate” nor “incoherent” but spoke fluently and competently in AAVE, with possible influences from Caribbean Creole English (CCE).

Their study details aspects of Jeantel’s speech that display features of AAVE grammar. Here are just a few examples (with the approximate SAE equivalents):

- Stressed BIN (been)

- “I BIN knew I was the last person to talk to Trayvon.” (had known for a long time)

- Habitual be

- “Sometimes my friends be texting for me, when I’m busy.” (my friends habitually text for me when I’m busy)

- Absence of the possessive -s

- “His daddy fiancée house” (his daddy’s fiancée’s house)

Had there been any African American jurors, Rickford says, Jeantel’s language would have more likely made perfect sense to them. Instead, the nearly all-White jury found her “hard to understand” and “not credible.”

Prescriptivism, privilege, and prejudice

Ignorance wasn’t the only thing preventing participants and onlookers of the trial from taking Rachel Jeantel seriously; they also displayed deep prejudice. The harsh judgments directed at Jeantel come from a deep-seated ideology that many educated and well-meaning people share: that “good” grammar following Standard American English is inextricably linked with intelligence, credibility, and even moral character.

The idea that there is a correct way to use language is called linguistic prescriptivism (as opposed to linguistic descriptivism, which is the study of how people use language). Prescriptivism can be useful for teaching a language, standardizing the jargon and style of a particular industry or academic field, or reforming outdated language conventions. However, a historical perspective of prescriptive grammar reveals that many of our ideas of “good” grammar are often arbitrary based on ideas of linguistic purity and an elitist obsession with Latin.

Linguistic prescriptivism is not only a mark of class, ability, and educational privilege, but is also, particularly in the United States, entangled with racist, xenophobic, and White supremacist attitudes. Prejudice based on someone’s speech is easy to pass off as an issue of comprehension rather than bigotry. This makes it all the more dangerous, because regardless of intention, it results in silencing voices of color and holding up the interests of people who are closer to the idea of “Whiteness.”

Patrick Jonathan Derilus, an American-Haitian independent writer, describes his journey of unlearning the prejudices he absorbed from his educational background like this:

“I was often self-demeaning when it came to my writing skills. I believed the only way that I would be understood was if I wrote ‘intellectually.’ […] Reading several Black authors helped me recognize that even before my time there were Black intellectuals, too, who were subject to having to meet the status quo as a means of validating their humanity. While our teachers have long introduced writing/speaking ‘proper’ English as a fundamental utility, they have, nevertheless, failed to unveil this approach to writing/speaking as an institutional system that is grounded in white supremacy.”

Black English matters

Language-based racism says that Black English is unintelligent, lazy, and broken. Thus, it puts Black people at a disadvantage in all areas of life, including housing, income, job markets, courtrooms, and classrooms. But Black English is a family of dialects as valuable and legitimate as any other. The language is a creative force that has contributed richly to cultural life and linguistic innovation throughout American history, whether it be in art, music, poetry, storytelling, or more recently, social media.

In this 2014 article, Dr. Wonderful Faison, who is now chair of the English Department at Langston University, shares her story of going from feeling shame about fellow Black people who had a difficult time with SAE grammar to celebrating the way she was raised to speak, concluding:

“If I said it befo’ I done said it a thousand times: If you cain’t take the BLACK off my face you sure cain’t take the BLACK off my tongue. My language is ME and I am my language. It lives. It moves. It breathes. To kill my language is to kill me. Period. Point blank. End of story. […]

“I was almost took. Almost hoodwinked. Almost bamboozled out of my language. But While I almost forgot, almost is still not quite. And now I remember, I remember that I use Black English or rather Spoken Soul because:

‘it is a language in which I feel comfortable… because it came naturally; because it was authentic… touching some time within and capturing a vital core of experience that had to be expressed just so’ (Rickford and Rickford 222).”

Linguistic diversity in education

As Patrick Derilus and Dr. Faison point out, educational institutions have for too long been teaching young Black students to feel shame about speaking in a dialect that brings them comfort and connects them to family, community, and heritage. Norms around teaching English and grammar also suggest that students who have had the training and exposure necessary to master the standard form of English that this mastery means that they are smarter, more worthy, and more respectable than those who have not. Under these circumstances, is it any wonder that harmful biases arise?

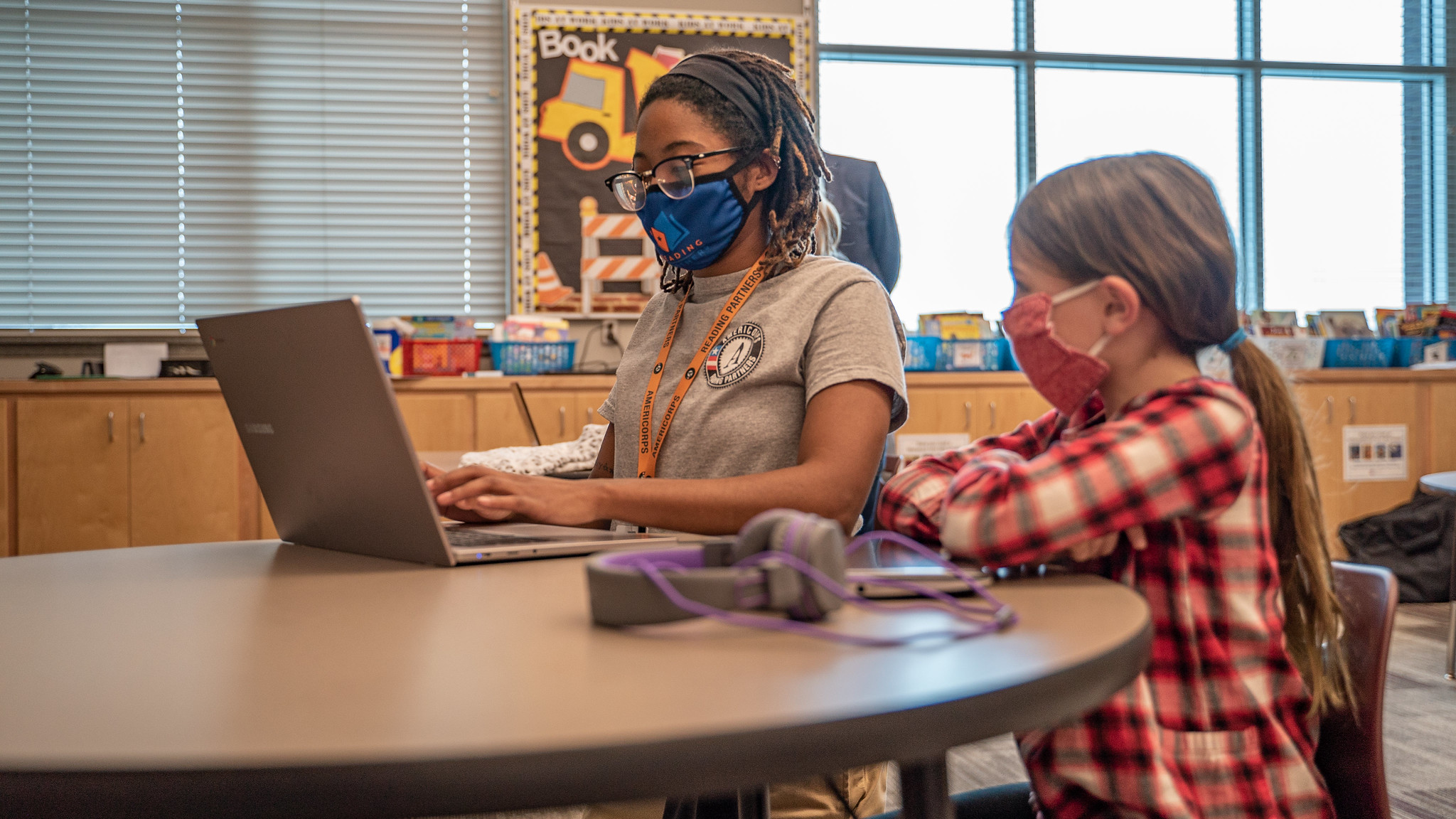

ELA classrooms, reading centers, and writing workshops often function to solidify our foundational beliefs about language. Educators in those spaces owe it to young people of all linguistic backgrounds to do more than teach them how to use the standard written dialect. Students also need opportunities to build familiarity with nonstandard dialects and have intentional discussions about language, as well as encouragement to express themselves freely in the dialect in which they are already proficient.

Working toward racial equity, diversity, and inclusion, especially in education, must involve acknowledgment that the English taught in schools is not the correct form of English but a particular dialect of English.

While Reading Partners’ core curriculum teaches students how to understand and use written SAE in recognition of its importance for their functioning in American society, we also recognize that there are many paths to literacy and becoming lifelong readers. We advocate for providing children with reading material that is relevant and interesting to them. We also strive to introduce our students to books that reflect the diversity of the world we live in, such as these stories from Goodreads that each showcase AAL, AAVE, or BVE in the characters or in their narration:

Virgie Goes to School with Us Boys by Elizabeth Fitzgerald Howard

The People Could Fly: The Picture Book by Virginia Hamilton

Flossie and the Fox by Patricia C. McKissack, Rachel Isadora

Yo! Yes? by Chris Raschka

She Come Bringing Me That Little Baby Girl by Eloise Greenfield

Kinda Blue by Ann Grifalconi

The Dark-Thirty: Southern Tales of the Supernatural by Patricia C. McKissack, Brian Pinkney

Big Jabe by Jerdine Nolen, Kadir Nelson

Working Cotton by Sherley Anne Williams, Carole M. Byard

Sources

- Header image: RF._.studio from Pexels

- African American English

- Zimmerman trial

- Racial profiling

- Features of Black English

- What Is African American Vernacular English (AAVE)?

- Why We Be Loving the “Habitual Be”

- AAL Facts

- Mapping Lexical Innovation on American Social Media

- Slate: Is Black English a Dialect or a Language?

- English grammar

- Language or dialect

- Educator resources

- Reading Partners Blog